Decred blockchain analysis - Part 1

Getting to know the Decred blockchain

I started exploring the Decred blockchain in more depth at the end of 2019 as I scoped out a plan for the third phase of the Open Source Research Program. With a local instance of dcrdata up and running, I watched it whizz through hundreds of thousands of blocks worth of data, creating tables representing every address, transaction, input, output, and vote - the origins and destinations of all the DCR in existence. There’s something satisfying about seeing all of the work it does to prepare that raw data for consumption through charts and tables.

After initial excitement about identifying different types of activity in the database and producing some rough early charts, I fell into a couple of rabbit holes related to making sense of this data. Clustering addresses and tracking what happens to specific sets of decentralized credits.

A key requirement to making sense of this data is knowing or inferring when DCR was changing hands, as opposed to moving within the addresses of a single holder. One way to do this is by checking whether the addresses being sent to are known to be associated with exchanges. jz kindly provided me with some starting addresses for all the major DCR exchanges, and after adding a few of my own I have expanded these to cover a few hundred thousand addresses as being associated with specific exchanges (still a work in progress).

At some point into mapping out the addresses used by exchanges, I realized that this task was deeply connected to the larger task of auditing stakeholder privacy, which would involve clustering addresses. When looking at an exchange’s transactions on chain, a key requirement is to know which outputs are withdrawals to customers and which are change outputs or internal transactions between the exchange’s own wallets. Recognizing addresses as belonging to clusters that do things like staking or mining means they can be identified as not belonging to the exchange.

Early progress with clustering

I found working through the code to piece all of this together to be pretty challenging, looking at “the chain” can have a disorienting effect, with all of those input and outputs flying between addresses that are virtually indistinguishable from each other to the human eye. A few have caught my eye though, like DshitsEnTq4….

After a lot of trial and error with the address clustering and “activity profiling” of these clusters, I am no longer finding significant errors when I work with the results. I’ll be nudging this along for some weeks through a list of address groupings of interest (PoW Miners, exchange depositors and withdrawers, big time PoS voters, contractors, and probably the mining pool and VSP operators too). Now that I’m over the hump and have code that works for this, I’m looking forward to building up an in depth history of the Decred chain.

Voting is a big part of that history, and provides some strong clustering heuristics. It also adds an interesting component to clustering and grouping of actors, because we can look at whether, and also how, they voted on a range of issues.

The mixing introduced in 2019 is effectively an end point to many of the stories that we can tell about actors on the Decred chain - once they start mixing the only thing I would be able to pick out (so far at least) is how much they put into the mixer.

I am also keen to wait until this mixing is more widely available (i.e. Decrediton integration released) before publishing too much about address clustering, because it is realistically the only way to avoid having one’s transactions all being associated quite easily by anyone who is motivated to do so.

Now that I’m not troubleshooting that code every few days, my attention has turned to polishing the graphs and writing this all up.

This first instalment covers a selection of more straightforward analyses I have seen used with other blockchains and found interesting to repeat for Decred.

Age of unmoved credits

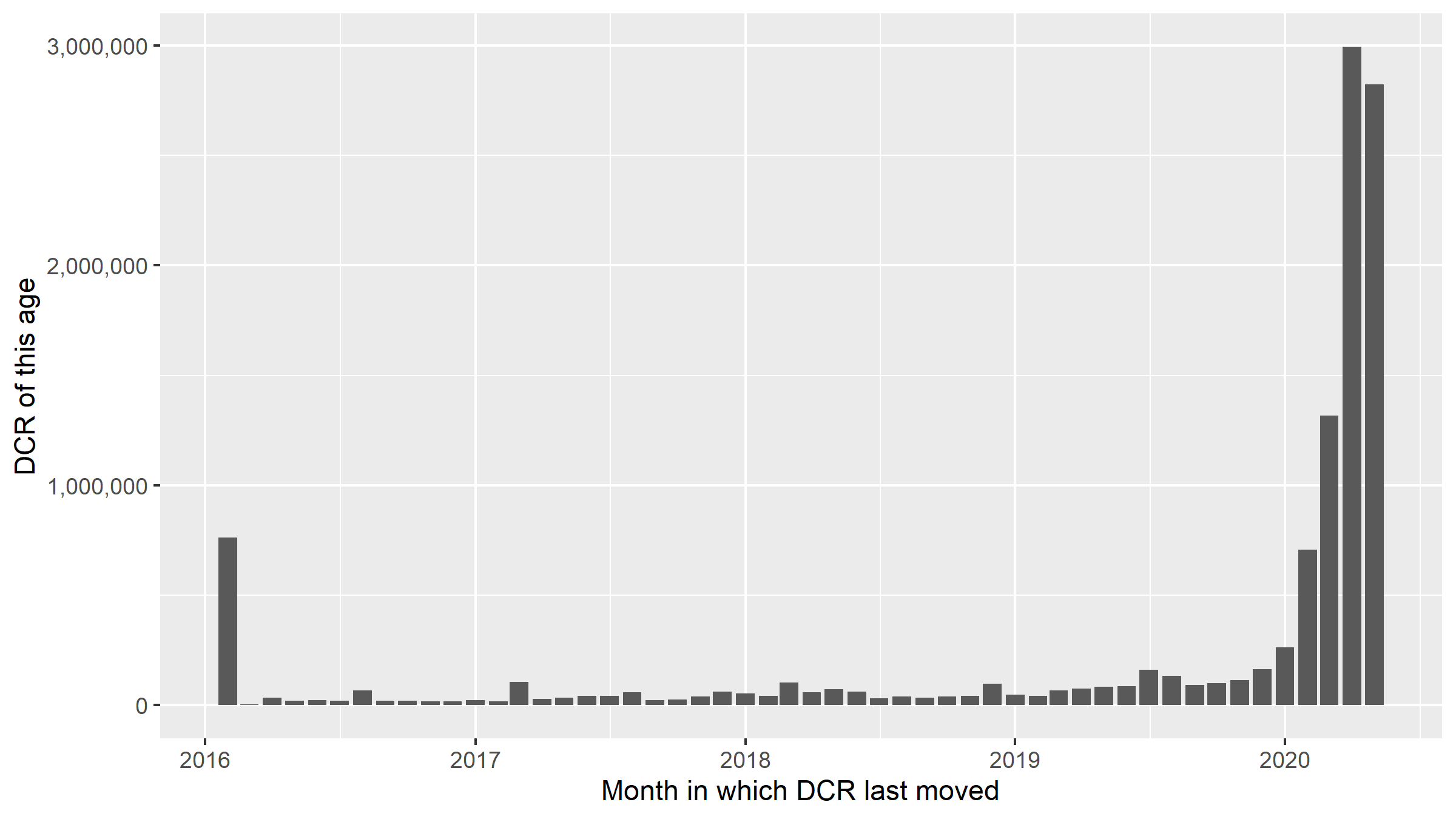

Let’s take a look at when all the unspent DCR (as of May 2020) last moved.

Month when all circulating DCR last moved

A lot of circulating DCR has moved in the last few months, which is no surprise to anyone who knows that about ~50% of it is participating in PoS.

The other significant presence on this chart is the premine of 1.68 million DCR, of which 762k remains unspent. As part of the premine, 4% of the eventual supply went to developers and 4% went to 2,972 airdrop participants. This allows those coins to be broken down into founder and airdrop coins.

465K of the Founders premine remains untouched, along with ~290k of airdrop DCR, or 1,024 airdrops. As someone who is relatively new to on chain analysis, I found it very interesting that you can get this information simply by looking at that transaction on dcrdata. Count up the rows with Spent == false and you will get the above numbers (or would have done on the day I wrote this).

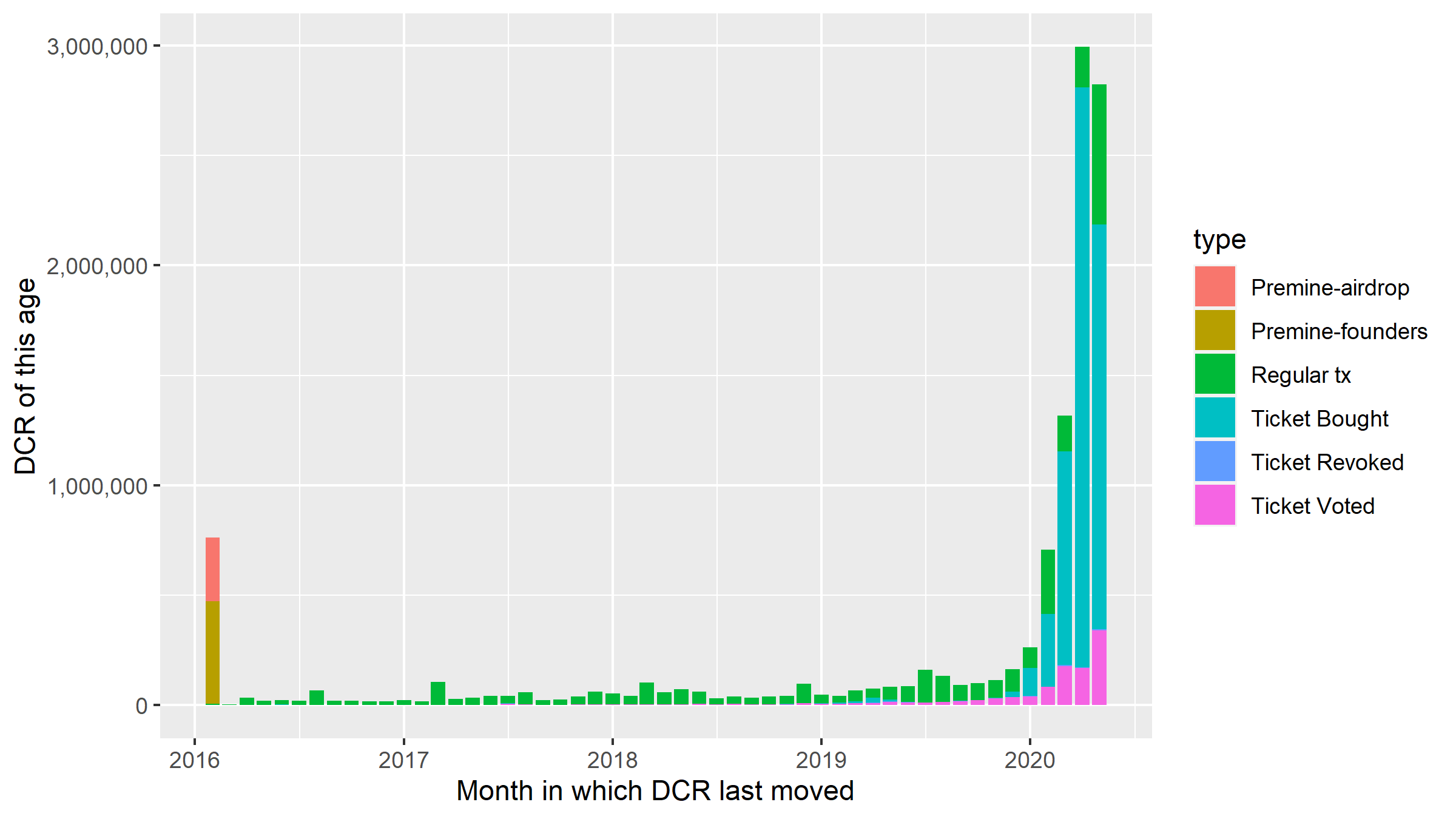

We can also look at all of the unspent DCR in terms of what its last transaction was, represented on the same graph below.

Month when all circulating DCR last moved (with type of last transaction)

The green segments on these bars represent the kind of regular transaction that makes up the entirety of a blockchain like Bitcoin’s. There has been a steady “flow” of DCR that stops moving and just sits there (long-term holders), with some DCR dropping out each month and what looks like annual peaks to this.

Distribution of unspent credits between addresses

Some addresses hold large DCR balances, and some just have a partial credit - and any number of different addresses might be generated by the same wallet. There are limits to how much information can be gained from looking at individual addresses, so I won’t spend much time on these now as this kind of analysis will be more interesting when performed with clusters.

First let’s look at where the DCR is. For these graphs the addresses have been grouped by their balance into bins, the axis labels (e.g. “10”) are the upper bounds of the bins (i.e. “1 to 10”).

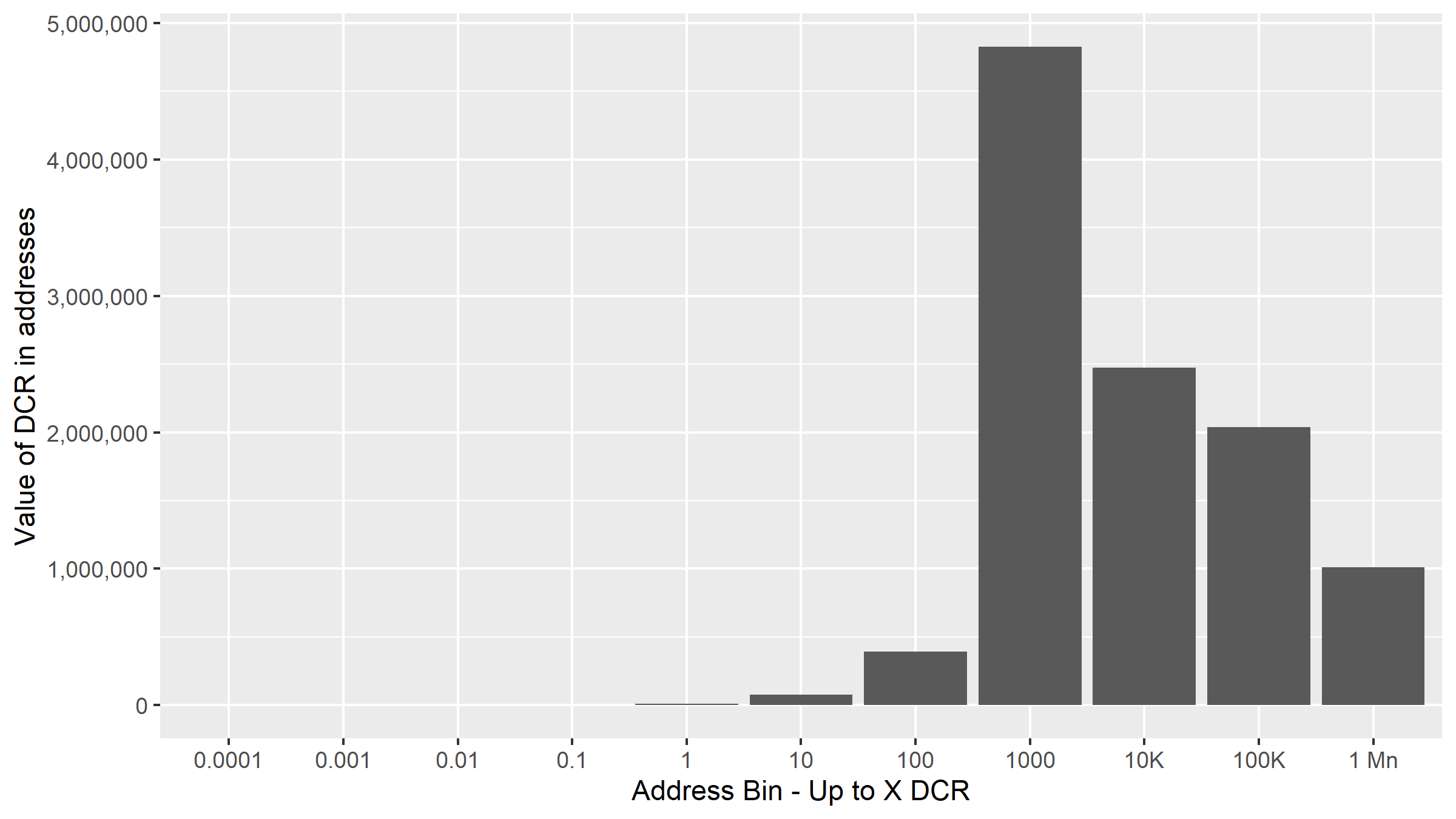

Unspent DCR by size of address balance

Most of the DCR in circulation (95%) is in addresses with balances of > 100 DCR. Address with balances of between 100 - 1,000 DCR is where 44.5% of circulating DCR rests, much of it likely related to transactions for buying tickets.

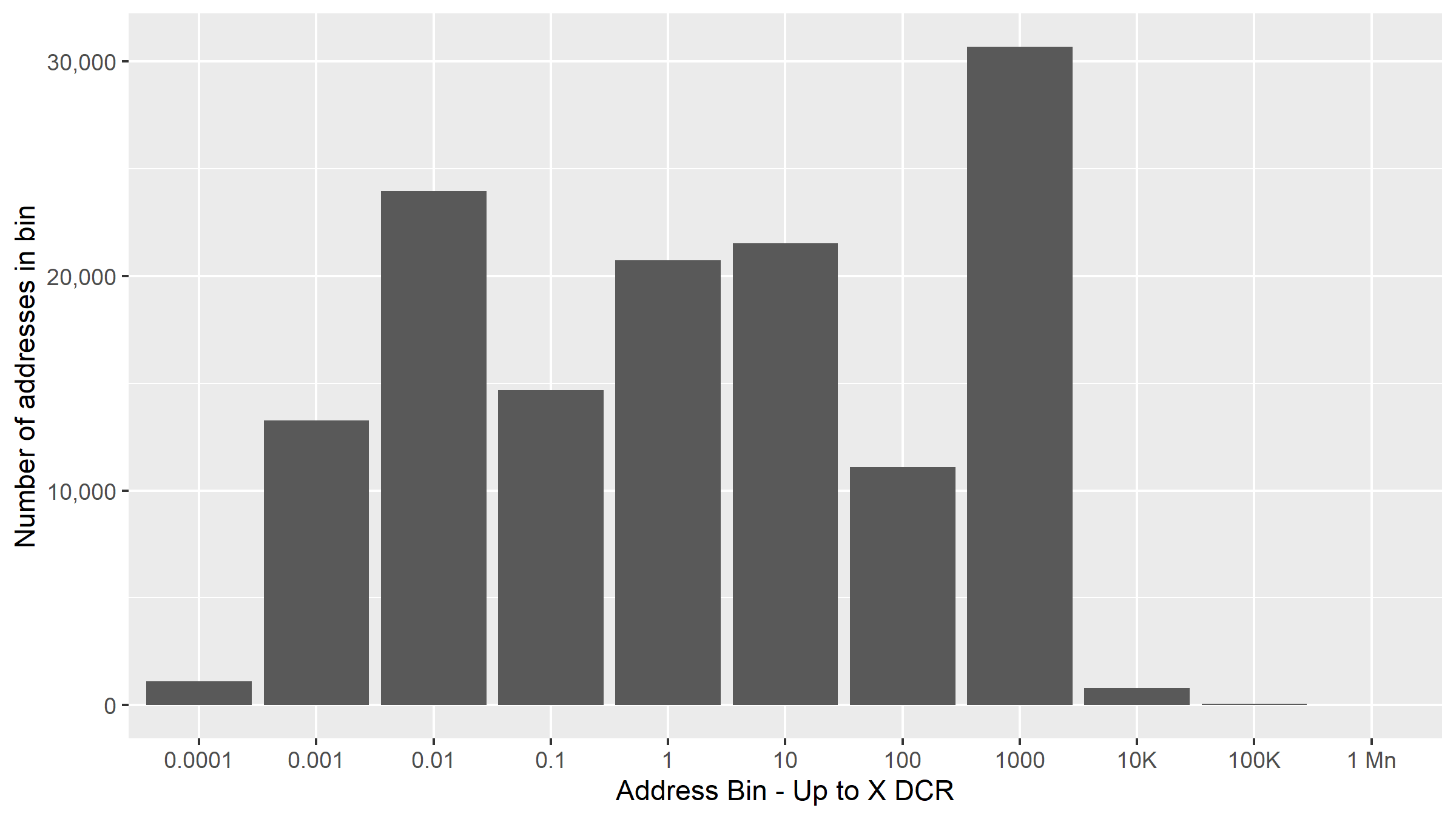

Number of addresses with unspent balance size

There are at the same time many addresses with small unspent balances, these include actions like payments to PoW miners and fees for VSP operators, which have a tendency to be stationary for some time before being spent.

Given that addresses do not represent individual actors or wallets, there is limited insight to gain from using measures like a Gini coefficient with this data. For Gini specifically the presence of a large number of distinct addresses with small balances would appear as a mass of impoverished citizens. I ran it anyway out of curiosity, the coefficient comes out at 0.88 for the full address data-set (without Treasury address, as this is a special case). It drops to 0.75 if the addresses with balance of less than 1 credit are excluded. These are numbers on the “high inequality” end of the scale. When the clustering work has progressed it should be possible to get a more meaningful Gini coefficient for Decred’s pre-mixing years using the data for clusters.

To echo a measure I have seen for Bitcoin (where it is 13%), Decred’s top 100 addresses by unspent balance (excluding Treasury) control 3.25 million DCR, or 30% of the circulating DCR (excluding Treasury balance).

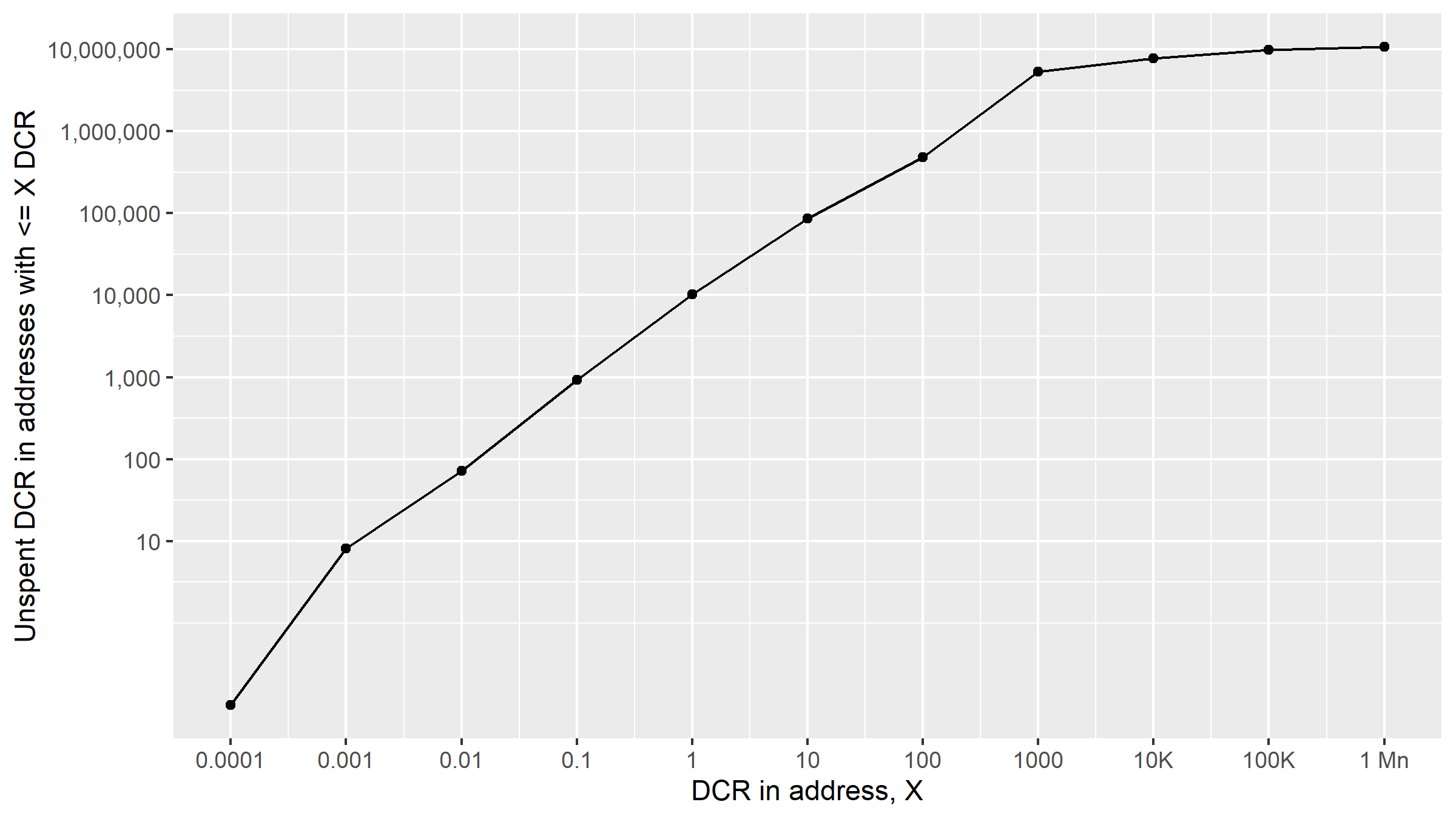

Unspent DCR cumulative distribution

This is the cumulative distribution of unspent DCR between addresses (addresses binned by order of magnitude again) with logarithmic transformation of both axes. A straight diagonal line on this kind of plot is indicative of a power law distribution. At the top end the large addresses have less DCR than would be expected under such a distribution.

Transaction action

The Decred blockchain (at the point my database is up to) records the details of 7.7 million transactions, of a variety of different types.

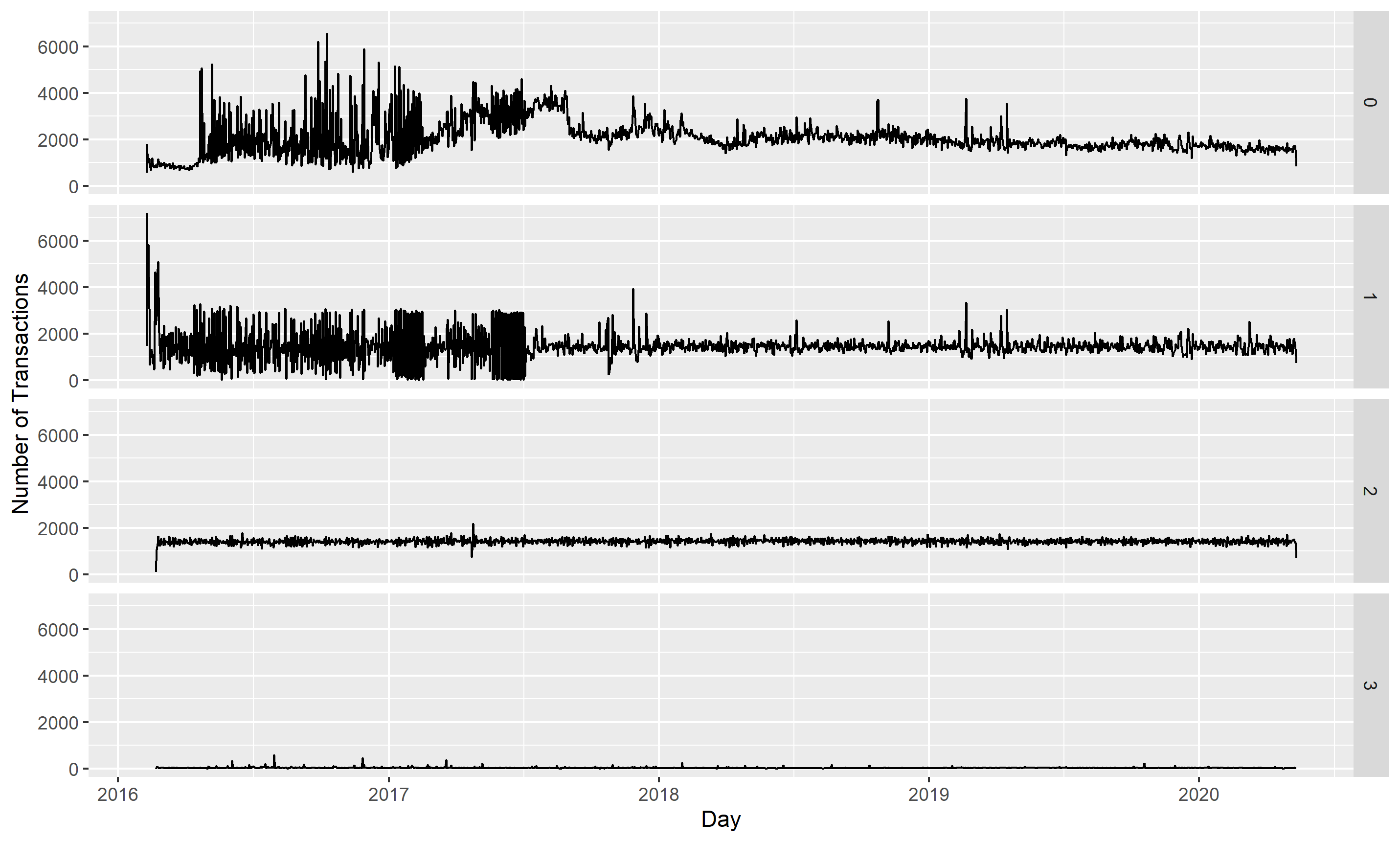

Transactions per day by type

This graph shows raw count of transactions per day for each of the 4 types that dcrdata uses to categorize transactions. Type 1 transactions involve buying tickets, Type 2 is voting and Type 3 transactions are revocations for expired or missed tickets. After early volatility in transaction counts associated with staking (due to the old ticket price algorithm, and ending once it was replaced in mid-2017), the pace of transactions became quite steady.

~58% of Decred transactions to this point in time have concerned staking, with 3.22 million transactions (41.6%) not directly related to staking.

Within this set of “type 0” transactions we can identify some more that are staking-related. Ticket purchase transactions (type 1) are almost always preceded by a standard transaction which sets up the purchase of 1 or more tickets by first preparing the precise inputs required to buy those tickets (ticket price plus mining fees plus possible VSP fee for VSP users).

There are 1,389,691 such transactions, which amounts to 43% of all the type 0 transactions, pushing the maximum number of transactions which had nothing to do with PoS down to 1.83 million.

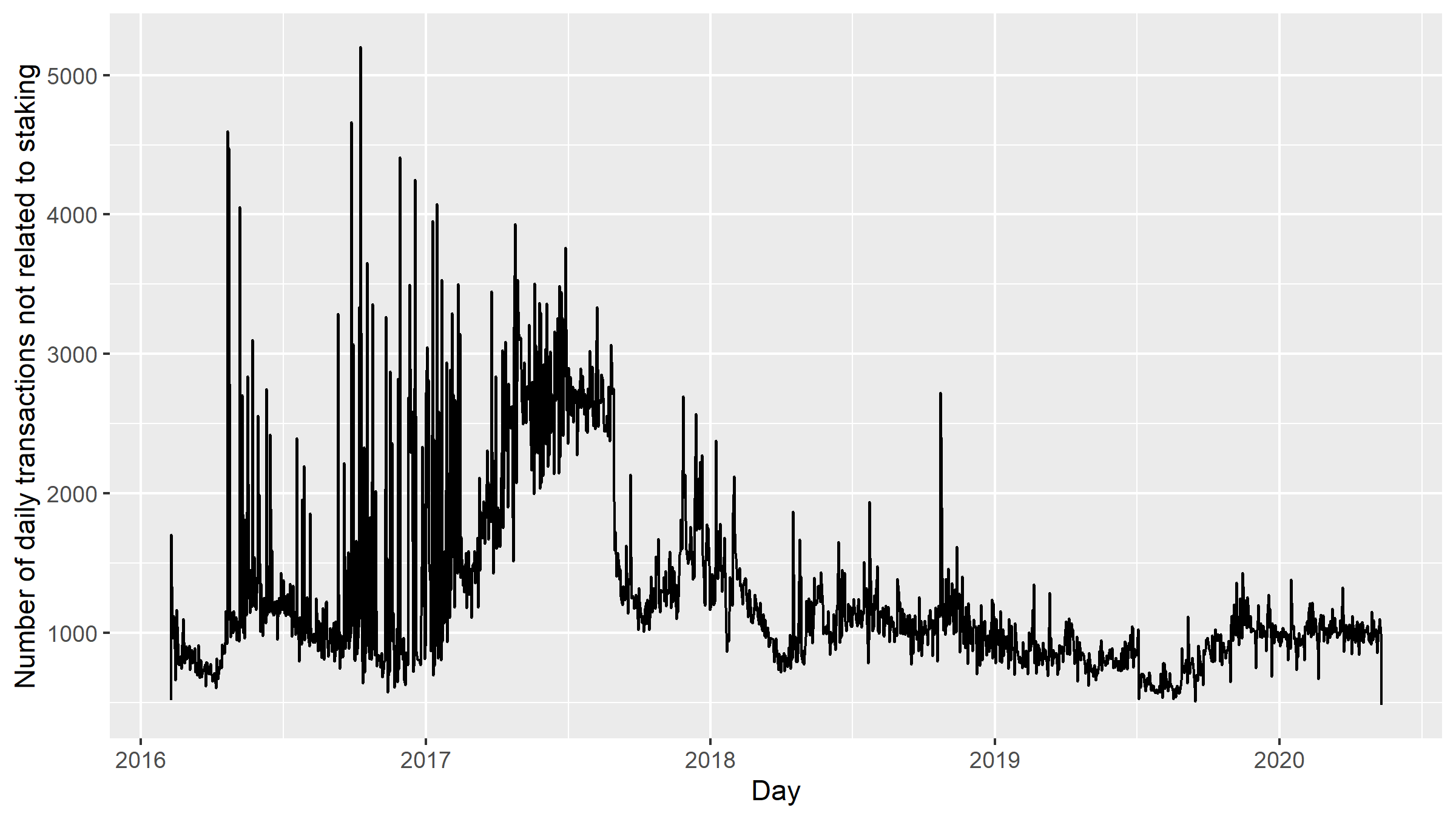

Non-staking-related transactions per day

Transaction taxonomy

I am building up a more comprehensive taxonomy of different transaction types and the ways to identify them in the dcrdata tables. This section considers the amount of space in the blockchain used by different types of transaction that are easily identifiable, and how much is being paid in fees to make these transactions.

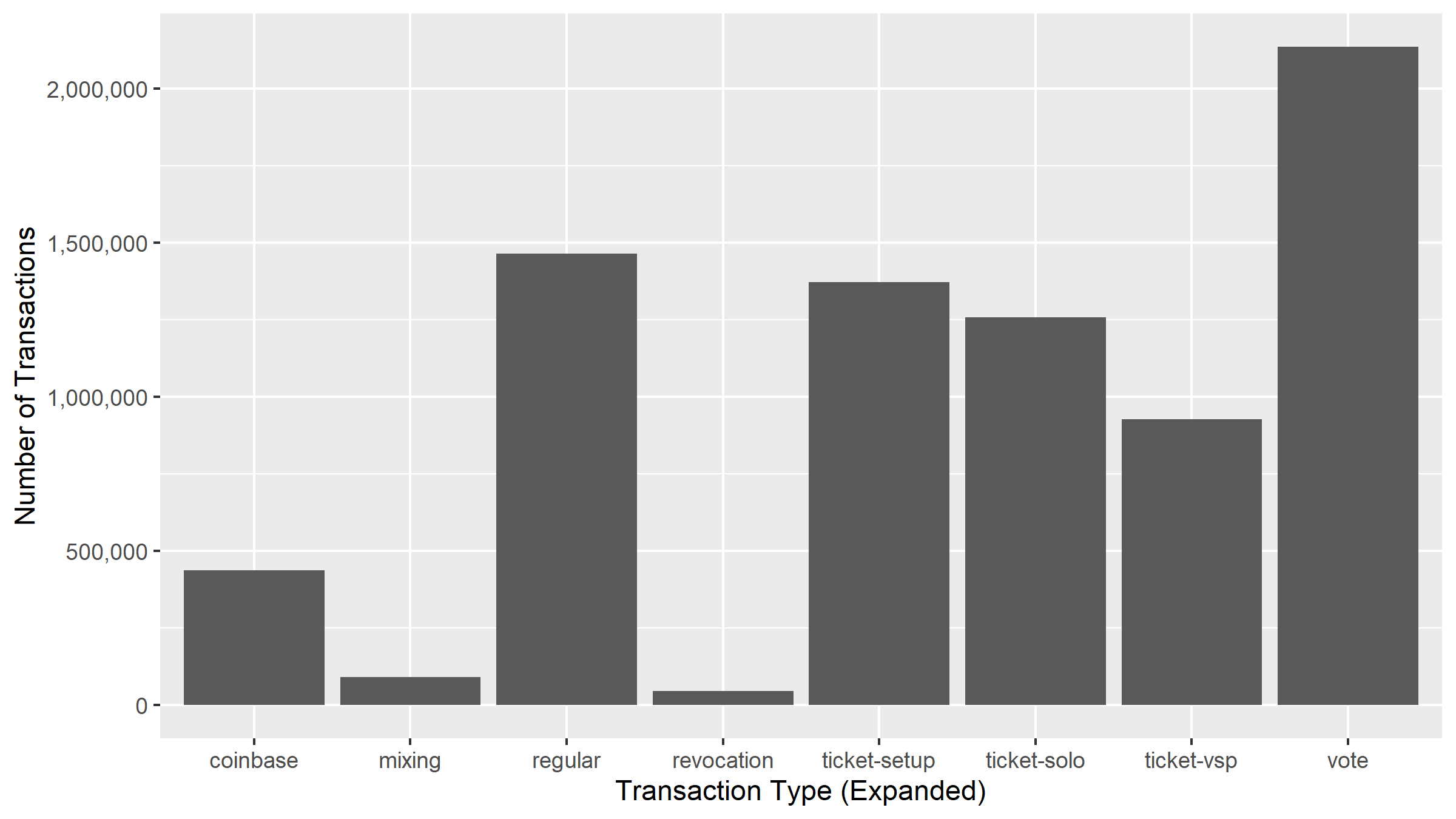

Number of transactions per type

This introduces the coinbase type of (regular) transaction and also splits mixing transactions out from regular transactions. It also differentiates between transactions used to buy tickets that by solo stakers from those of VSP users (dcrdata has a field for this in its tickets table). Over the full history of the Decred chain, there have been more solo voted tickets.

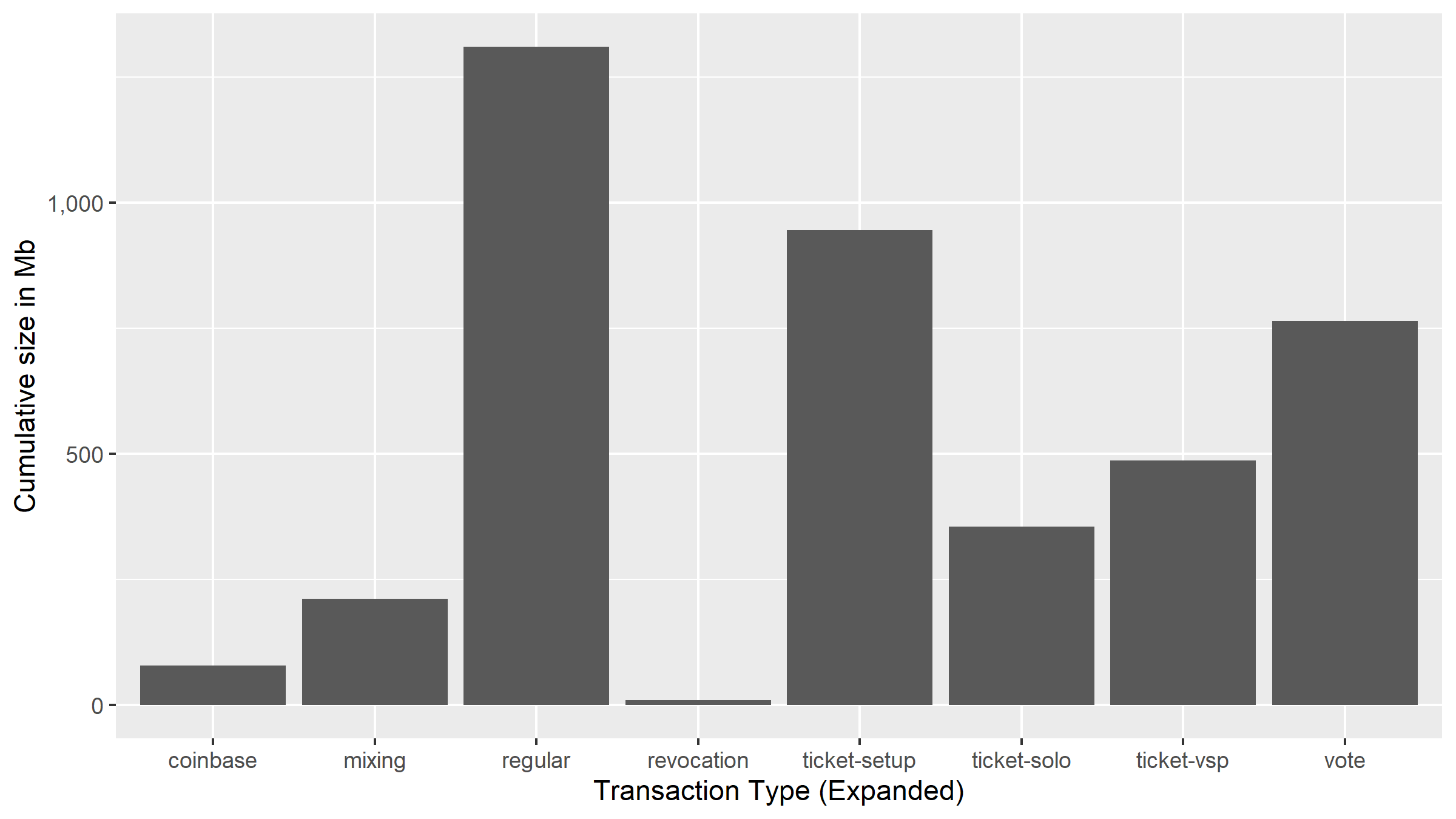

Size of all transactions per type

This graph shows the amount of space occupied by data about different types of transactions. Considered with the previous graph, it can be inferred that ticket and voting transactions are smaller than average regular transactions, and that transactions to buy tickets with a VSP are larger than those for solo voting tickets.

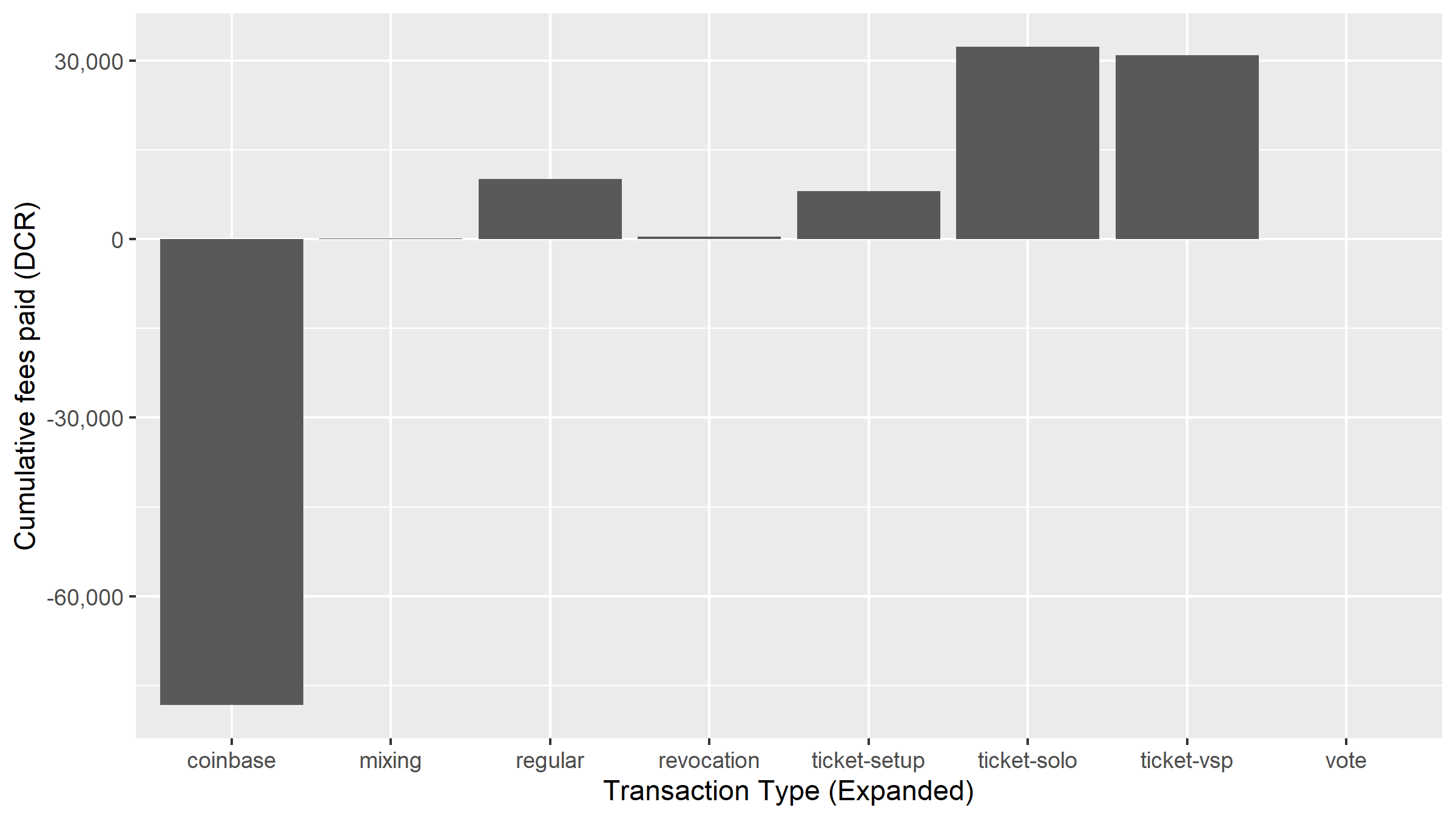

Fees paid for transactions per type

Here the negative bar for coinbase transactions is showing that PoW miners have received 78,300 DCR in transaction fees over the history of the Decred chain. Considering the 6 million DCR PoW miners have received from new issuance, fees have accounted for about 1% of miner revenue. The graph above shows that most of the fees are related to ticket-buying transactions. They also relate primarily to the earlier part of Decred’s history, where the original ticket price algorithm produced volatility and led to competition to have ticket-buying transactions accepted by miners. This chart on dcrdata shows that most of this fee action happened in the first few years.

There are other sorts of type 0 transaction which can be identified, like those associated with PoW mining pools and VSP operation, or depositing/withdrawing DCR from exchanges. The clustering work uses these as flags to determine which type of actor the cluster represents, and should be able to build up a more intelligible picture which cuts out a lot of noise of inputs and outputs flying between lots of addresses to look specifically at the relations between address clusters that probably represent different actors.

Taint tracking

In addition to the clustering techniques, “taint tracking” is one of the aspects I have spent the most time on. This involves taking a set of addresses or transactions and asking how that DCR was used. While it can be hard to know whether some transactions reflect transfer of DCR between holders or within a holder’s own addresses - some transactions have a very clear interpretation. Using the DCR to buy a ticket is an obvious outcome, it’s easy to detect and has a clear meaning - they’re holding and want to participate in governance, don’t mind locking their credits.

Sending DCR to an exchange address is another obvious kind of outcome, it means that whoever held it previously probably sold it. Once it comes out the other end of however the exchange handles DCR within its own addresses, the DCR will likely be in the hands of another holder. Detecting when DCR is sent to an exchange on chain means knowing which addresses belong to exchanges, there is nothing else to identify these transactions.

Taint tracking means following a particular set of outputs (like payments from the Treasury to contractors below) through several “hops”. The way transactions branch out to include multiple inputs and outputs makes this quite difficult, it requires keeping track of which proportion of the original “taint” has gone into which transactions, so that when an “outcome” is reached a few hops down the line we know how much of the original payment which it came from that outcome accounts for.

Treasury/contractor spending

This analysis is based on a data snapshot taken before the latest Treasury payouts in May 2020, while the total DCR spent was 344,689. The figures are based on following the taint of these transactions for 3 hops. This is still perhaps not 100% reliable, because it’s using a new method that processes all the transactions at once and considers the timing of when the outcomes occurred. I first developed a method which is based on following each output individually, but this takes much longer to execute.

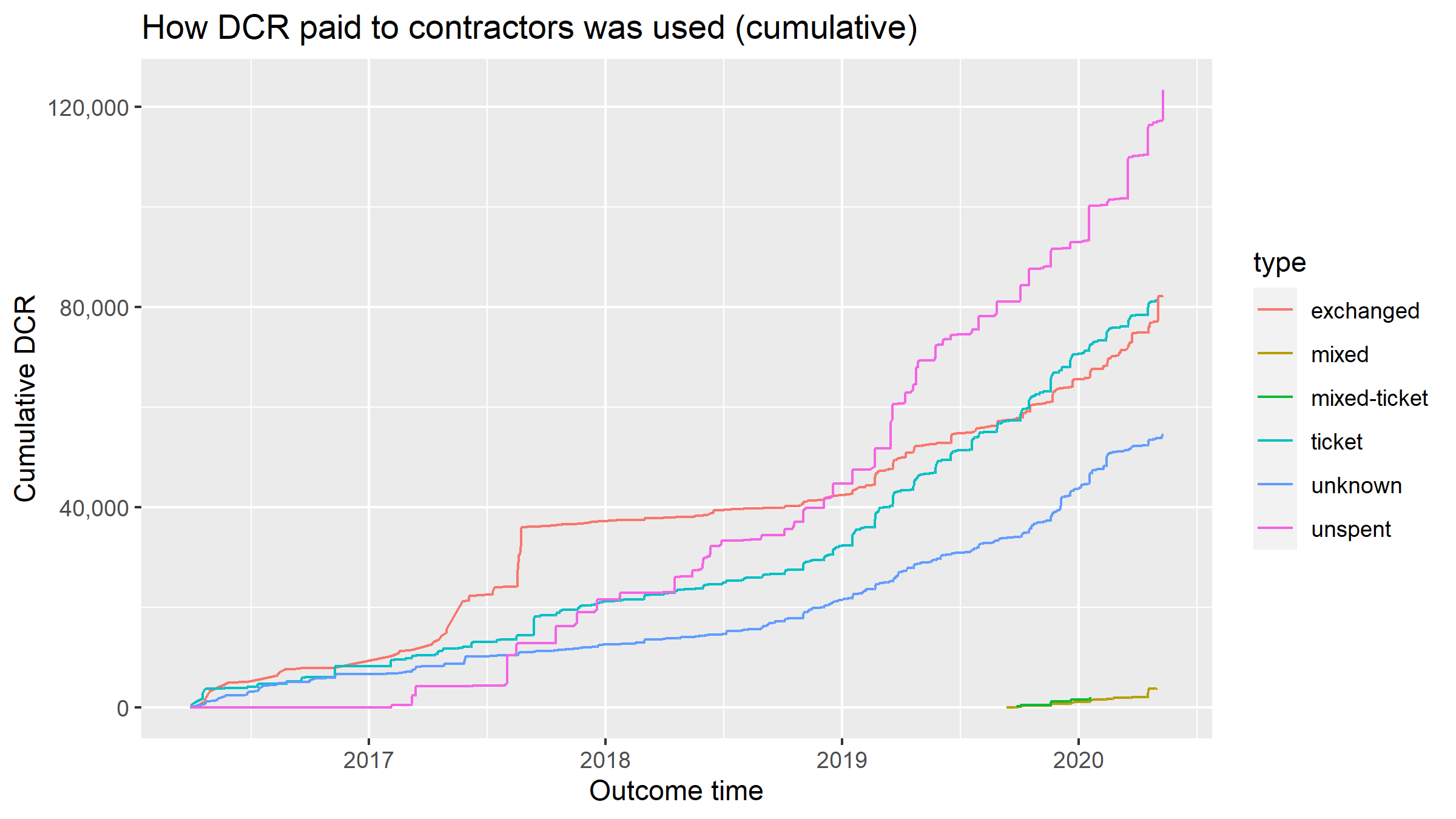

Outcomes for Treasury payments to contractors

-

92,640 DCR paid out by the Treasury (~27%) has not been touched since the contractor received it. A further 30K of Treasury payments are moved at least once before remaining unspent - likely being held long term by the contractor, or possibly someone who they sold to directly. In total 35.5% of DCR paid out by the Treasury is unspent without having been staked or sent to a known exchange address.

-

23.7% of the DCR paid out by the Treasury ended up in a known exchange address. At least one of the contractors appears to use an exchange address directly on their invoices.

-

23.5% of this DCR has been staked, almost certainly by the contractors who received it.

-

1.7% of the DCR received by contractors was mixed, including 0.5% that was mixed in ticket-buying transactions.

-

15.7% of the DCR being tracked was still moving after 3 hops and so its fate is unknown.

The proportion of unknown outcomes can be further reduced by following for more hops - although this would increase the chance the contractor traded with someone else through some untracked means along the way and would thus mis-classify the outcomes. The unknown outcomes can also be reduced by adding more exchange addresses to the table which is used to check for these. There are some smaller exchanges for which I have as yet no addresses, and I am not yet bringing in data from any decentralized exchanges which list DCR.

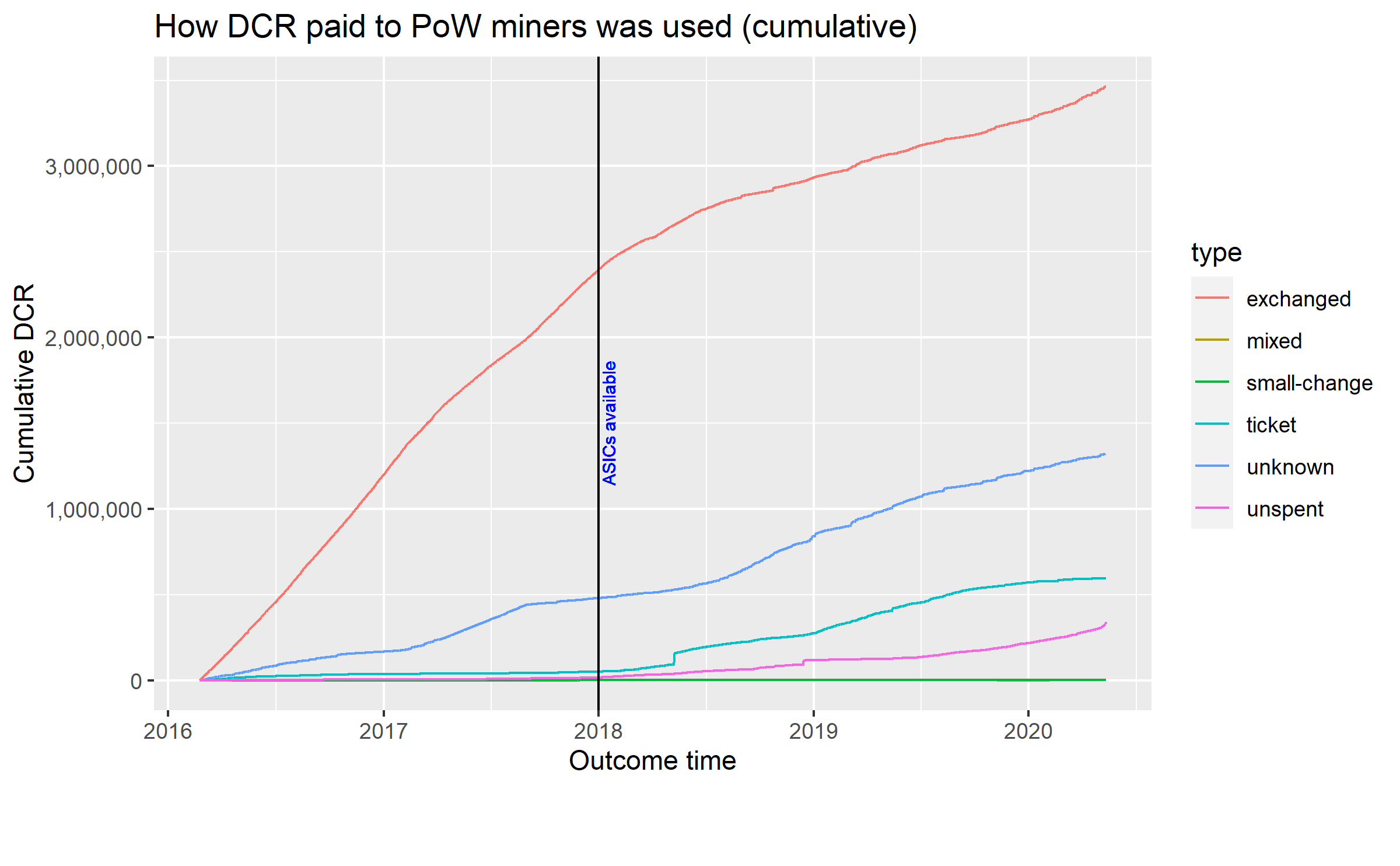

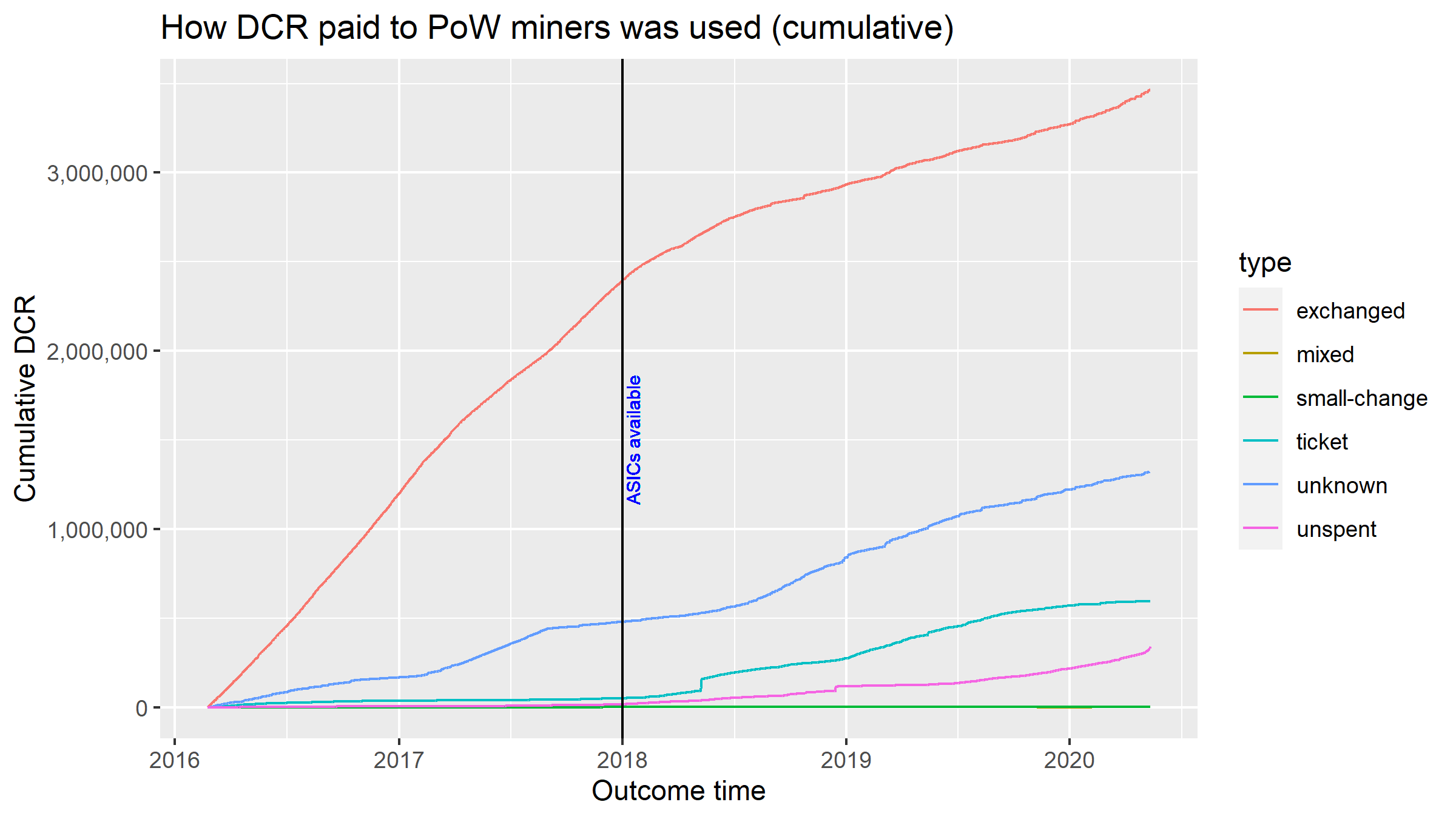

PoW miner spending

This one is fresh out of the R terminal, so handle with care. With the PoW miner rewards I found a need a follow the taint for more hops, because for miners that use pools there will be some hops associated with the reward moving from the coinbase to the pool to their mining address and then maybe consolidating into another address before being used to buy a ticket or sent to an exchange. I followed the PoW reward taint for 5 hops, or until it reached an outcome. As there are many more transactions involved, I had to prune the data-set down as I moved through the hops to avoid memory issues. I discarded transactions where there was less than 0.1 DCR of PoW reward taint being tracked, you can see the DCR this accounts for as a line at the bottom of the graph below.

At the point the database was up to, PoW miners had received a total of 5.8M DCR (block subsidy and transaction fees).

- 60% of the rewards have ended up in addresses associated with exchanges

- 10% has been staked for PoS tickets

- 6% is sitting unspent somewhere within the first 5 hops

- The equivalent of 5 somewhat-freshly mined DCR has been mixed. Miners don’t seem to mix.

- For 24% of the PoW miners’ rewards, I’m still not sure what became of them. OTC desks and lesser known exchanges probably account for some of this.

Outcomes for Treasury payments to contractors

This is based on the block time of the transactions where I detected an outcome. The outcomes occur at varying delays after the rewards were issued in a coinbase transaction, the graph shows the pieces of taint being added on as outcomes are reached.

The big event here was the shift from GPU mining to ASICs. In the early period merge mining with ETH was popular. There was speculation that miners would be selling the DCR to help cover costs, and that is supported by this data. Around the start of 2018, Decred’s hashrate started to increase as ASICs were manufactured, tested, and sold by a number of companies. By the time of the first Decred Journal issue covering April 2018, there are already reports of units being received and shipping dates for other models in late April or early May. There is a clear increase in the amount of mined DCR being staked or held at around this time, suggesting that some of the early ASIC miners were mining to acquire DCR so they could buy tickets.

The subject of miners and contractors selling DCR is often discussed in the Decred community as putting downwards pressure on price. This analysis suggests that miners are responsible for significantly more DCR directly hitting exchanges (3.46 million), as compared to contractors who are paid by the Treasury (~80K). It should be noted though that outcomes marked as staked are not being followed beyond the initial ticket buy. At the moment the analysis does not track how many times these rewards were staked or for how long, they could be staked once then sold or the miner could still be staking it now. These are the type of question that the clustering work should allow me to address.

Coming soon

At the moment I’m running and polishing my clustering and tracking code, with the aim to push this to a point where I can put almost all of the addresses that have been used into clusters that say something about where their DCR came from, where it went, and whether they staked or mixed it. The main thrust of this project is now putting those pieces together into a history of the Decred chain, while looking out for any additional clues that could be used to find weaknesses in the privacy offered by mixed DCR.